The Art of Adaptation in “Adaptation”

Vice-President Fidel Tan kickstarts our publication Exposure by exploring Spike Jonze’s meta-dramedy film, Adaptation, based on Susan Orlean’s 1998 nonfiction book The Orchid Thief.

Known for its self-reflexive narrative and ingenious use of metafiction, the 2002 film Adaptation has cemented its legacy in cinema as an iconic contemporary film by critics and audiences alike. Directed by Spike Jonze and written by Charlie Kaufman, the film serves as a commentary on the act of adaptation—from written texts to the big screen. Indeed, since its early days, cinema has always looked closely at literary works for inspiration. From Pride and Prejudice to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the history of classic novels begetting classic films goes a long way. While some film adaptations are strikingly similar to their source material, others assert their creative liberty by distancing themselves from the text.

Adaptation originates from screenwriter Charlie Kaufman’s venture to adapt The Orchid Thief, a non-fiction book written by author Susan Orlean about her investigation of plant dealer John Laroche. Vexed with his unsuccessful attempt to adapt the book, Kaufman is hit with a case of severe writer’s block. In a master stroke of flipping the script, he inserts himself and this exasperating adapting endeavour into the film’s narrative. This way, his struggle of adapting The Orchid Thief collapses onto the narrative of Orlean’s book itself, thus transforming an unfinished script into an unlikely but perfectly functional adaptation in its own regard. Dudley Andrew foregrounds the bounded relationship between film and text, saying that a film adaptation “owes something to the tale that was its inspiration” (Andrew 372). Unlike Andrew, I think the need to assess a film adaptation by its faithfulness to its source material can be counterproductive, and I argue that Adaptation is a clear example of how a film can simultaneously honour and distinguish itself from the text. In this essay, I will discuss more on the concept of adaptation and explain why film and text should be viewed independently of each other. As an extension of this discussion, I will also question auteur theory’s act of centring the director as a film’s principal author and explore the perspective of the screenwriter as the alternative auteur of cinema instead, particularly in the context of the film Adaptation.

Andrew delineates three modes of adaptation: borrowing, intersecting, and fidelity of transformation. Borrowing foregrounds an adaptation’s invocation of “new or especially powerful aspects of a cherished work” (374). This mode celebrates the stature of esteemed literary texts. By tapping on the pre-established presence of the source material, the film adaptation expands its reach and adds value to an ongoing cultural conversation. Thus, the film is a perpetuation of a “continuing form or archetype in culture” (374). The intersecting mode is characterised by its intentional rejection of assimilation, or as Andrew terms: “refraction of the original” (375). Unlike adaptations of the borrowing mode—actively entangling themselves with the source material—adaptations of the intersecting mode uphold the originality and distinctiveness of the literary text. Lastly, fidelity of transformation considers the reproducibility of cinema to faithfully replicate literary works. Andrew is particularly concerned with how films capture the “spirit” of the text, referring to a composite of an original work’s “tone, values, imagery, and rhythm” (376).

While each mode presents its own unique approach in adapting, it is important to acknowledge how ultimately, they all put the original text on a pedestal and look at them with deep veneration. Indeed, film adaptations are almost always enjoyed, examined, and critiqued in relation to the text they are based on. This inseparable entanglement of text and film renders a subconscious but burdensome expectation that the film adaptation should be faithful to the text. An analysis of Adaptation reveals how this expectation is limiting, restricting both artists and audiences to a narrowed vision of what adaptations can or should be. In its full lawless and postmodern glory, Kaufman’s Adaptation simultaneously emulates and repudiates Andrew’s three modes of adaptation all at once. Firstly, the film seemingly follows the rules of borrowing. Kaufman goes above and beyond to honour Orlean and her writing—albeit in the most uncustomary way possible—by writing her directly into his screenplay. This meta insertion of Orlean into Kaufman’s narrative is radical, forcing audiences to acknowledge not only Orlean’s writing of The Orchid Thief, but also her writing process, and the motivations behind her writing. Orlean, in Kaufman’s screenplay, is given focus as a writer, but not just as any author but the very author of the film’s source material. Thus, the cultural status of Orlean and her book is elevated, just like how adaptations of the borrowing mode extend the cultural legacy of their source material.

Adaptation can also be read as an adaptation of the intersecting mode, made conspicuous by Kaufman’s very inability to adapt The Orchid Thief. Kaufman does not assimilate Orlean’s text into his screenplay. Every moment of Kaufman’s hesitance and confusion is written into the film, and this self-reflexive portrayal of Kaufman’s adapting process becomes a cinematic representation of how Kaufman “records [his] confrontation” (374) with Orlean’s text. Ironically, Kaufman adapts The Orchid Thief into the filmic form by emphasising its unadapted state. Thus, Adaptation can be seen a refraction of The Orchid Thief, embracing its originality in its purest form by leaving it untouched. As the film progresses, it becomes increasingly fictionalised. Stepping away from Susan Orlean’s own factual account, Kaufman fabricates details of his Orlean and Laroche characters and manufactures his own narrative. While one might argue that this departure from truth demonstrates how Kaufman fails to capture the spirit of its source material, the real-life Orlean herself thinks otherwise, claiming that the film is “very true to the book's themes of life and obsession, and there are also insights into things which are much more subtle in the book about longing, and about disappointment” (Orlean qtd. in Perry). Indeed, Adaptation is committed to the spirit of Orlean’s book. Even in his own shortcomings in adapting the book, Kaufman still manages to pick out the book’s central themes and repurposes them in his own ingenious approach.

While Kaufman seems to adhere to the three conventional adaptation modes as put forth by Andrew, the film is also a conscious rejection and violation of these conventions in itself. In particular, the layering of frame narratives topples the traditional notion of adaptation where films appropriate meaning from a prior text (Andrew 373). The frame narrative of Laroche plays out similar to how the character appears in Orlean’s book, but when this narrative collides with Kaufman’s own frame narrative of himself adapting the book, the film becomes hyperaware of its identity as an adaptation. Consequently, Kaufman actively challenges these supposed conventional truths on adaptations. While Adaptation does honour its source material, its self-reflexive construct absolves it from being a conventional adaptation, one that simply looks to the text to construct its narrative. Kaufman charts his own path, constructing a postmodern film adaptation which exists separately from the text it adapts.

Instead of assessing adaptations through the comparison between book and film, perhaps one should view the adaptation discourse as a comparison between interpretations instead. To contextualise the idea in this essay, what we interpret of The Orchid Thief is different from what Kaufman interprets, and by extension, what he adapts and writes into his screenplay. Hence, the insertion of his thought process into the film serves as an inventive way to illuminate the idea that what the audience can work with is already filtered through the lens of the adapter. Indeed, the fidelity of adaptations is dependent on the adapter’s own interpretation of the text, which can be understandably different from the average audience member. If so, it is counterproductive to pick apart at length on how faithful a film adaptation is to the text, simply because fidelity is such a subjective concept to begin with.

The disintegration of the fidelity argument repositions the divisions established in adaptation discourse. As Kaufman has demonstrated, no longer is the adapted necessarily limited by the constructs of the original. Kaufman’s screenplay overrules this traditional hierarchal structure by transforming the original and the adapted into interchangeable entities. Kaufman’s self-reflexive turn allows him to move away from Orlean’s book, free from the suffocating need to be faithful to the original text. The further the distance from the source material, the more original his narrative becomes. But it is also precisely this distance which illuminates the essence of The Orchid Thief, a tale on longing and passion as Orlean claims. Kaufman achieves this by projecting these themes onto his own adaptation process. This renders an intertextual depth to Orlean’s book, emphasising its construct as a recount of Laroche’s story, or perhaps, an adaptation in its own regard.

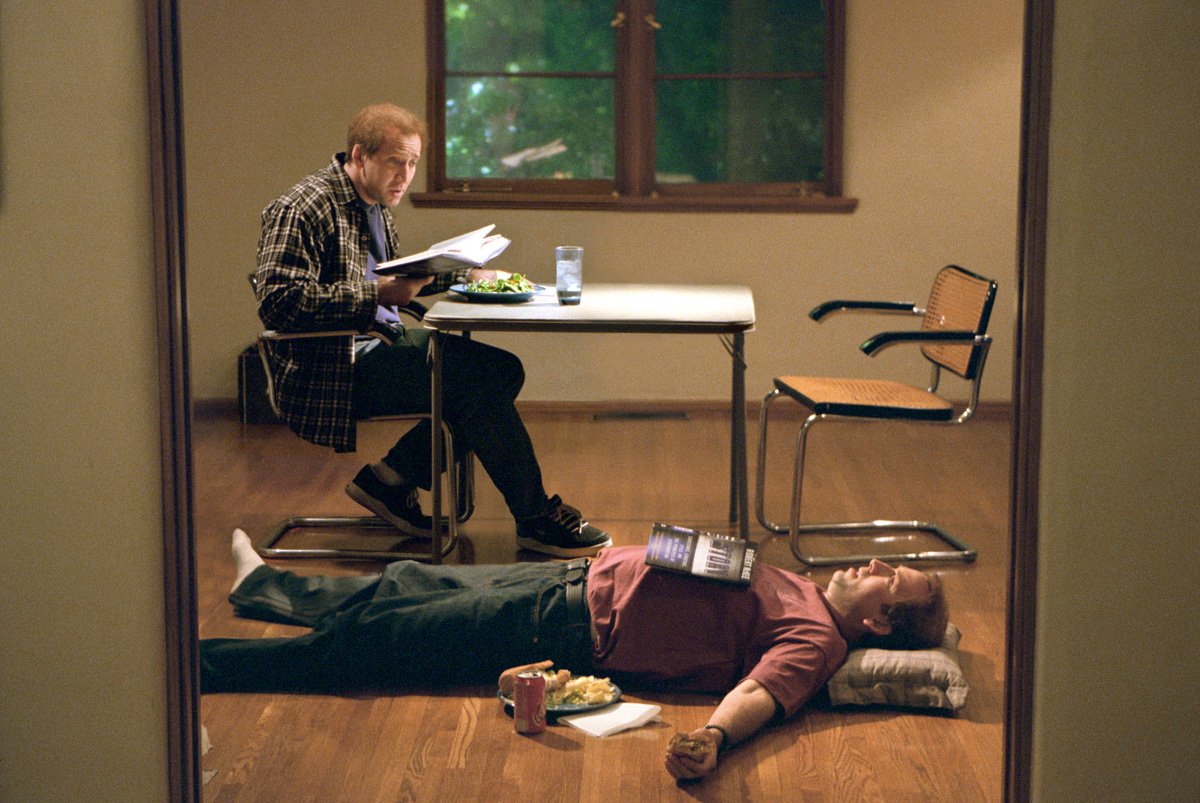

The act of writing himself into the screenplay doubles Kaufman’s authorial agency—firstly in the screen as the narrator–protagonist driving the story forward, as well as behind the scenes as the film’s sole screenwriter. This conflation of narrative voice and creative agency is critical, not only allowing Kaufman to assert his point of view in his writing but also see a cinematic representation of himself in Nicolas Cage’s Kaufman, one where he projects his thoughts and ideas on. As Kaufman takes charge of Adaptation’s narrative, I question the validity of auteur theory, particularly the centring the director as the principal author of a film. Coining the term “auteur theory” in 1962, Andrew Sarris is firm in his belief that the director gives a film its distinctive quality (561). By elevating the director as cinema’s sole originator, screenwriters are deliberately excluded from this celebration of art. In my opinion, Adaptation is an apt example to topple this belief. A quick scouring of academic discourse on the film shows how it is often prefixed as “Kaufman’s Adaptation”, even though the film’s director is Spike Jonze. This is not an isolated case; other famous screenwriters like Aaron Sorkin and Paul Schrader can attest to the phenomena of being hailed as auteurs of films they wrote but did not direct. Indeed, the proliferation of auteur theory has shaped the dominant perception that the film’s principal author is the director himself, rendering the screenwriter obsolete in cultural discussion. From the recognition of the film as “Kaufman’s Adaptation” to the foregrounding of Kaufman’s screenwriting process in the film’s narrative, Adaptation proves Sarris’ auteur theory otherwise—the screenwriter may be the auteur too.

Two decades since its release, Adaptation continues to be an enduringly popular film among cinephiles. Its postmodern tendencies are striking, from its rebellion against conventional beats of adaptations to its restructuring of the screenwriter as a film’s creative voice. Kaufman’s act of transforming a non-fiction account lacking in a narrative into a layered and intertextual film has revolutionised the very concept of adaptation itself. The film not only explores Orlean’s book, the field of film adaptations, and the act of adapting, it also becomes a mirror for Kaufman, reflecting his authorial agency onto a canvas that is his own screenplay. The result is a film so inherently about, for, and made by Kaufman, that has now been immortalised in the contemporary film canon as “Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation”.

Adapted from an essay Fidel wrote for his class on Film Theory (HL3001)Works Cited

Andrew, Dudley. “Adaptation.” Concepts in Film Theory, vol. 14, no. 3, 1986, p. 91.

Jonze, Spike, director. Adaptation. Sony Pictures Releasing, 2002.

Perry, Kevin EG. “The New Yorker's Susan Orlean on Crafting a Story and Being Played by Meryl Streep in Adaptation.” British GQ, British GQ, 16 Apr. 2012, www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/susan-orlean-adaptation-orchid-thief-rin-tin-tin.

Sarris, Andrew. “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962.” The Film Artist, p. 561-564.